Dr Martin Lally

Capital Financial Consultants Ltd

30 November 2021

Abstract

Covid-19 vaccine mandates for the general population must trade off the rights of those who object to being vaccinated against the costs that the unvaccinated impose upon the vaccinated, most particularly the increased risk to vaccinated people of death by covid-19. This paper provides a methodology for doing so. It is then applied to the case of New Zealand. It reveals that even if the adverse impact of penalties on vaccine objectors (many of whom may have rational grounds for objecting) were as small as a reduction in their quality of life of 1% per year for a period of five years and the existence of unvaccinated people were entirely responsible for covid-19 infections amongst the vaccinated, the number of additional deaths amongst the vaccinated resulting from not adopting a vaccine mandate would be too few to justify a policy of mandating. However, unlike the general population, health workers come into frequent and close contact with large numbers of sick people, who are prime targets for covid-19, and therefore the vaccine mandate may be justified for these workers. This rationale does not apply to education workers, who are even less likely than the general population to come into frequent and close contact with people at high risk from covid-19.

The helpful comments of Michael Reddell, John Haywood, Lyndon Moore, Damon Collin, Richard Frogley, Jack Robles, Robert Kirkby, Rodney Hide, Grant Schofield, and Ian Harrison are gratefully acknowledged. Agreement with the paper is not implied.

Introduction

Vaccine mandates for the general population are proving to be extremely controversial. Opponents point to the right to choose whether to be vaccinated, and to concerns over the safety of the vaccine. Proponents point to the costs that the unvaccinated impose upon the vaccinated, in particular the increased risk of covid-19 to vaccinated people (because the vaccine is imperfect) and the increased load on the public health system from unvaccinated people seeking treatment for covid-19 leading to some (vaccinated) people receiving an inferior level of care for non-covid conditions than they otherwise would and thereby dying earlier than they otherwise would.[1] An important benchmark in assessing mandates involves actions that are clearly beneficial both privately and socially, and free of adverse private or social consequences, such as the use of car seat belts. Accordingly, the first requirement here is to assess whether vaccine mandates are of this kind. If so, they would be justified. If not, then this would be another example of the trade-offs we face in life, individually or socially, and is therefore capable of being illuminated (and possibly resolved) by cost-benefit analysis. This paper seeks to do so for New Zealand, which has imposed significant penalties on those failing to vaccinate.

The Rationality of Vaccine Opposition

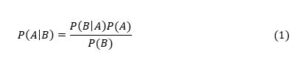

Consider the case of a 80+ year old person. For this group, Verity et al (2020, Table 1) gives an Infection Fatality Rate (IFR) for covid-19 of 7.8%, i.e., a probability of death if infected of 7.8%. Application of this Verity et al (2020, Table 1) data to New Zealand’s population proportions by age group yields an overall population-wide IFR of 0.95% (Steyn et al, 2021, page 14). By contrast, recent literature surveys suggest population-wide IFRs of 0.3 – 0.4% for Europe and the Americas (Ioannidis, 2021, page 10), and 0.70% for Europe and 0.58% for the Americas (Meyerowitz-Katz and Merone, 2021, Figure 2). The midpoint is about 0.5%, which is approximately double the figure of 0.95% implied by the Verity et al (2020) data. So, I halve Verity et al’s figure of 7.8% to yield an IFR of 3.9% for an 80+ year old. Death rates from covid-19 also depend upon the health status of the individual, with the risk of death (if infected) being higher for those with various pre-existing conditions. Bayes Theorem states that the probability of event A occurring conditional upon B occurring is the probability of B occurring conditional upon A occurring multiplied by the unconditional probability of A divided by the unconditional probability of B (Mood et al, 1974, page 36), i.e.,

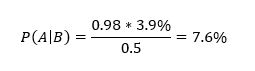

In this case, A means death from covid-19 and B means suffering from a relevant pre-existing condition. So, P(A) = 0.039. Most covid-19 deaths involve people suffering from serious pre-existing conditions. For example, in respect of those dying in New York City up to 13 May 2020, in those cases where the existing medical condition of the patient was known (no underlying condition or at least one underlying condition), 98% had at least one underlying condition (the set of conditions includes diabetes, cancer, heart disease, lung disease, and hypertension).[2] Furthermore, this probability is similar across age groups. This means P = 0.98. In respect of P(B), this is the probability of an 80+ year old having any of the relevant pre-existing conditions. Such conditions are common amongst 80+ year olds and I therefore assume P(B) = 0.50. Substituting these parameters into equation (1) yields:

So, a randomly selected 80+ year old would have a probability of dying from covid-19 if infected of 3.9%, rising to 7.6% if they suffered from any of the relevant pre-existing conditions, i.e., 1/13. This is without vaccination. The vaccines reduce the risk of death by 85% to 88% on average over the first six months but rapidly wane beyond that point (Nordstrom et al, 2021, Table 2 and Table 5). So, if vaccinated with boosters, the probability of death falls from 7.6% to 7.6%*0.15 = 1.14%, i.e., 1/88. So, vaccination reduces the risk from 1/13 to 1/88. The absolute reduction in risk is very large.

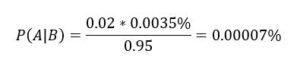

I now consider the case of a 10-19 year old who is not suffering from any of the relevant pre-existing conditions. So, A still means death whilst B now means not suffering from any such conditions. For a 10-19 year old, Verity et al (2020, Table 1) gives P(A) = 0.007%, which is halved to 0.0035% as above. Also, P = 1 – 0.98 = 0.02. In respect of P(B), this is the probability of a 10-19 year old not suffering from any of the relevant pre-existing conditions. Such conditions are rare in 10-19 year olds and I therefore adopt a probability of them all being absent of 0.95. Substituting these parameters into equation (1) yields:

So, a randomly selected 10-19 year old would have a probability of dying from covid-19 if infected of 0.0035%, falling to 0.00007% if they did not suffer from any of the relevant pre-existing conditions, i.e., 1/4.3 million. This is without vaccination. The vaccines reduce the risk of death by 85% to 88% on average over the first six months but rapidly wane beyond that point (Nordstrom et al, 2021, Table 2 and Table 5). So, if vaccinated with boosters, the probability of death falls from 1/4.3 million to 1/28 million. The absolute reduction in risk is very small.

Table 1 shows these results and others, for the unvaccinated. In moving from the first to the last age group, the probability of all relevant pre-existing conditions being absent is assumed to decline linearly from 95% for the first group to 50% for the last group.

Table 1: Risk of Death from Covid-19 if Infected and Unvaccinated

_______________________________________________________

Healthy Not Healthy

_______________________________________________________

10-19 1/4,300,000 1/1,500

20-29 1/290,000 1/750

30-39 1/100,000 1/440

40-49 1/48,000 1/300

50-59 1/11,000 1/100

60-69 1/3,300 1/40

70-79 1/1,300 1/20

80+ 1/625 1/13

_______________________________________________________

All vaccines have some side-effects, which could include death. A rational person will weigh these risks against the personal benefits of the vaccine (reduced risk of their death from covid-19). The blinded, randomised, placebo-controlled studies submitted in support of the vaccine being approved were very favourable to the vaccine, but the sample sizes were too small to detect adverse side effects at the very low rates that would still make them worse than the risk of death by covid-19 in young healthy people. For example, Pollack et al (2020) reports on a study by Pfizer, involving 44,000 participants of which half were given the vaccine and half a placebo. Covid-19 was diagnosed in considerably more cases in the placebo group than the vaccinated group (162 to 8), but the only subsequent deaths in either group (six participants) were judged to be unrelated to covid-19, the vaccine, or the placebo. However, suppose the risk of death from the vaccine were 1/50,000 and independent of age or health. This risk is entirely consistent with the absence of any such deaths amongst the 22,000 participants given the vaccine, but Table 1 reveals that such a risk would exceed the risk from covid-19 amongst healthy people under the age of 45.[3] So, Pollack et al (2020) does not provide any confidence that the risk of death from the vaccine is less than that from covid-19 for healthy people under the age of 45.

Pollack et al (2020) also reports four cases with serious side effects, all of them in the vaccinated group. This is a rate of 1/5,000. Standard cost-benefit analysis for health issues involves discounts to Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) for imperfect health status. Beaudet et al (2014, Table 3) estimates quality of life discounts for various medical events, none of which appear in Pollack’s set. Using an average discount of 10% over the conditions reported by Pollack, the 1/5,000 risk of such conditions arising from the vaccine is equivalent to a risk of death of 1/50,000. Table 1 then implies that (leaving aside the risk of death) it would then be rational for any healthy person under the age of about 45 to decline the vaccine if these risks of serious side effects were not age or health related.[4] Coupling this risk of serious side effects with whatever the risk of death is, the threshold age below which vaccination is not optimal would be even higher than the figure of 45 estimated in this paragraph.

An alternative source of information on the side effects of the vaccine is the reports by government entities on all vaccinated people. These reports involve much larger numbers of participants but lack the statistical controls of blinded, randomised, placebo-controlled studies. Medsafe (2021a) reports 97 deaths following the vaccine of which one was likely due to the vaccine, six were still under investigation, 43 were unlikely to be due to the vaccine, and 47 could not be assessed due to insufficient information.[5] In recognition of the uncertainty here, Medsafe (2021b) also compares actual deaths amongst the vaccinated within 21 days of a dose with the expected number of deaths, with the latter based upon data from 2009-2018 (the “natural death rate”), and finds that actual deaths are lower (600 versus 1,100). Prima facie, this suggests that the vaccine is not causing deaths. However, the fact that the actual deaths are below rather than equal to the expected deaths (and markedly below) reveals that the prediction model is poor or things other than the vaccine are significantly affecting the death rate, and therefore the vaccine could be inducing a moderate number of deaths that are masked by these other phenomena. For example, suppose the vaccine had induced 34 deaths amongst the 3.4 million people vaccinated to date in New Zealand, which is not inconsistent with Medsafe’s disclosures. This implies a risk of death of 1/100,000, and Table 1 implies that it would be rational for any healthy person under the age of 35 to decline the vaccine if the risk from the vaccine were not age or health related. However, 34 deaths is far too small a number to be detected by the actual to expected comparison undertaken by Medsafe (2021b). So, Medsafe’s disclosures on risks of death provide no confidence that the risk of death from the vaccine is less than from covid-19 for healthy people under the age of 35.

Medsafe (2021a) also reports 1,200 “serious adverse events” following vaccination that are suspected to be due to the vaccine, up till 30 October 2021, none of which involved death. These include strokes, heart attacks and facial paralysis. Across the 3.4 million people vaccinated up until this point (half the number of doses administered), this is 1/2,800. Standard cost-benefit analysis for health issues involves discounts to Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) for imperfect health status. Beaudet et al (2014, Table 3) estimates quality of life discounts for various medical events, of which heart attack and strokes appear in the Medsafe list, with discounts of 11% and 16% respectively. Using an average discount of 10% over the conditions reported by Medsafe, the 1/2,800 risk of such conditions arising from the vaccine is equivalent to a risk of death of 1/28,000 (which is equivalent to 120 deaths amongst the 3.4 million people vaccinated). Table 1 then implies that it would then be rational for any healthy person under the age of about 50 to decline the vaccine if these risks of serious side effects were not age or health related.[6] This represents the majority of New Zealand’s population.

Coupling this risk of serious side effects with whatever the risk of death is, the threshold age below which vaccination is not optimal would be even higher than the figure of 50 estimated in the previous paragraph. I do not imagine that most or perhaps even any of the vaccine objectors have performed this kind of analysis on the vaccine risks. Instead, I expect that they would instead simply have a sense that they were not at any material risk of death by covid-19 but felt that the risks from the vaccine were likely to be higher. The analysis and examples here are consistent with such thinking.

This analysis presumes that vaccine objectors trust official sources of information. Medsafe’s (2021a) report is based upon reporting by patients and health workers, and the serious adverse events are presumably reported by doctors. Medsafe (2021a) asserts that “The protective benefits of vaccination against COVID-19 far outweigh the potential risks of vaccination.” However, Medsafe does not perform or cite any analysis in support of this conclusion, and the analysis above suggests that the assertion is false for most New Zealanders. Medsafe’s assertion then looks like cheerleading rather than impartial reporting of adverse events. A related problem occurred with the elimination strategy pursued by the government, in that its external advisers continued to publicly support this strategy even after the only cost-benefit analysis carried out by any of them on elimination versus mitigation revealed that mitigation was preferable (Lally, 2021a). All of this could reasonable lead some people to doubt official sources of information.

This analysis also presumes that vaccine objectors ignore the benefit to their fellow citizens from them being vaccinated, i.e., the reduction in the risk of highly susceptible vaccinated people becoming infected as a result of the existence of unvaccinated people, and subsequently dying. However, rationality does not require selflessness. In addition, vaccine objectors could reasonably believe that all vaccinated people will eventually become infected through transmission amongst vaccinated people and therefore there would be no social benefit from them (the objectors) being vaccinated.

In conclusion, the risks of death from covid-19 if infected are so low for healthy adults under the age of 50 (less than 1/30,000) that such people could rationally prefer not to be vaccinated purely on the basis of the number of serious (but non-fatal) side-effects from the vaccine that have been reported to date by Medsafe. Additionally allowing for even a low possibility of death from the vaccine strengthens the case amongst such people for not being vaccinated, and further allowing for even moderate scepticism about official sources of information further strengthens the case.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Having established that many people might rationally object to the vaccine, I now undertake a cost-benefit analysis on the mandating of it. Let N denote the number of people in a country who object to being vaccinated against covid-19. Standard cost-benefit analysis for health issues involves discounts to Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) for imperfect health status. For example, a person suffering from type 2 diabetes without complications warrants a discount of about 20% per year of their remaining life (Beaudet et al, 2014, Table 3). The same principle applies to a vaccine mandate, i.e., it reduces the quality of life of those objecting to being vaccinated. For some of these people, the effects of the penalties for non-vaccination may extend to all of their remaining lives. This might occur because the objector has given up a preferred job rather than being vaccinated. Alternatively, having acceded to being vaccinated because of the penalties, the objector is then subject to what they believe to be the risk of vaccine side-effects that exceeds the reduction in their risk of dying from covid-19, and they may also suffer from anxiety over these future risks, and from anxiety over the possibility that the vaccine has caused a health condition that they experienced at some point after being vaccinated.[7] The mandating of vaccine boosters would aggravate these effects for objectors who were induced into being vaccinated. For other objectors, the effects of the penalties would fade quickly. In recognition of the latter group, I (conservatively) adopt a horizon of five years for the quality of life effects of penalties on all objectors. Let W denote the average annual discount on the quality of life of objectors arising from the penalties. The QALYs lost from a mandating policy is then N*5*W.

Now consider the costs that the unvaccinated impose on the rest, of the types mentioned above. Let D be the expected additional deaths amongst vaccinated people from the existence of unvaccinated people, if mandating is not adopted compared to being adopted, and with minimal other measures to contain the virus. The deaths here are of people likely to have low residual life expectancies and health problems that would lower their quality of life had they not died from covid-19. Lally (2021b, section 2.2) estimates the average residual life expectancy of the covid-19 victims (had they not died from covid-19) as five years for European countries and the discount for health problems during this five-year period at 20% per year. The QALYs lost amongst vaccinated people from failure to adopt a mandating policy is then D*5*0.8, i.e., D*4. There will also be QALY losses amongst vaccinated people who survive the infection but suffer significant symptoms for a protracted period (long covid), but Lally (2021b, pp. 17-18) finds that this contributes very little to the QALY losses from deaths.

In summary, if vaccine mandating is adopted, the N people alive today who object to being vaccinated will experience a QALY loss of N*5*W whilst the vaccinated avoid a QALY loss of D*4. So, mandating is warranted only if D*4 exceeds N*5*W.

Application to New Zealand

I now apply this cost-benefit model to New Zealand. Penalties for failure to vaccinate in the form of loss of employment have already been introduced for some categories of workers, including those in health and education, and there are plans to apply lesser penalties to the general population over the age of 12.[8] Approximately 84% of the New Zealand population (of 5 million) is in the 12+ group.[9] This constitutes 4.2 million people. As of 15 November 2021, 10% of this group had not yet had a first dose (420,000) and yet had ample opportunity to do so by that time. These people can therefore reasonably be viewed as vaccine objectors. In addition, some of those vaccinated up until this date are likely to have done so because of or in anticipation of penalties. So, the set of New Zealanders who object to being vaccinated (N) is at least 420,000.

In respect of the average annual discount on the quality of life of people subject to penalties for not being vaccinated (W), this average will reflect considerable variation across objectors. Taking account of the fact that a person suffering from type 2 diabetes warrants a discount of about 20% per year of their remaining life (Beaudet et al, 2014, Table 3), a value for W of at least 1% per year is plausible.

Conditional on W being 1% per year, mandating would then be warranted only if D*4 exceeds 420,000*5*0.01, i.e., D exceeds 5,200. This means 5,200 additional deaths amongst vaccinated people (from covid-19 or from other conditions arising from unvaccinated people overloading the public health system with covid-19 symptoms), if mandating is not adopted compared to it being adopted. In respect of the public health system being overloaded by unvaccinated people with covid-19 symptoms, any society willing to impose significant penalties upon the unvaccinated would presumably be willing to apply a much lower level of health care to them should they experience covid-19 symptoms, which would significantly mitigate the health system overload. Overload can also be further mitigated by expanding the capacity of the health system.[10] This suggests that the principal adverse effect of the unvaccinated upon the vaccinated is the additional deaths amongst the vaccinated arising from being infected with covid-19 because of the existence of unvaccinated people (who are likely to increase the spread of the virus). So, vaccine mandating would be warranted only if failure to do so leads to a pool of unvaccinated people who thereby induce at least 5,200 additional deaths from covid-19 amongst the vaccinated.

I now consider whether at least 5,200 additional such deaths amongst the vaccinated could occur. The worst case scenario for the 90% of the over 12s who vaccinate without mandating (4.2m*0.9 = 3.8m) is that they all become infected as a result of the existence of the unvaccinated people who could be induced into vaccinating by penalties. In the absence of an effective vaccine, the proportion dying is the Infection Fatality Rate (IFR). Recent surveys suggest figures of 0.3 – 0.4% for Europe and the Americas (Ioannidis, 2021, page 10), and 0.70% for Europe and 0.58% for the Americas (Meyerowitz-Katz and Merone, 2021, Figure 2). The midpoint is about 0.5%, which implies 3.8m*0.005 = 19,000 dead. However, this IFR relates to the entire population rather than only those over 12, and the latter IFR would be higher because the IFR is monotonically increasing with age. Correction for this raises the IFR for the over 12s to about 0.60%.[11] This implies 3.8m*0.006 = 23,000. The vaccine reduces the risk of death by 85% to 88% on average over the first six months but this rapidly wanes beyond that point (Nordstrom et al, 2021, Table 2 and Table 5). If a booster is used at that point, the average reduction in the death rate would then be at least 85%. This implies 23,000*(1 – 0.85) = 3,400 deaths amongst the vaccinated.

This is the worst case, and is unlikely to occur for three reasons. Firstly, it is unlikely that all of the 3.8m vaccinated would be infected. Secondly, amongst those infected, it is inconceivable that all would be infected as a result of the pool of unvaccinated people, i.e., some of the vaccinated would be infected even if there were no unvaccinated people because the vaccine does not eliminate the risk of its recipients transmitting the virus and therefore vaccinated people could be infected by other vaccinated people.[12] In fact, all of the vaccinated might become infected even if the unvaccinated pool did not exist, through the virus transmitting through the vaccinated. Thirdly, amongst those vaccinated who were infected as a result of the unvaccinated pool, some would be infected as a result of the vaccine objectors who will not accede to vaccination despite the penalties, and this group exists regardless of whether a mandating policy is adopted. Taking account of all three of these points, the additional covid-19 deaths amongst the vaccinated in the absence of vaccine mandating would be significantly less than 3,400.

An even lower figure is implied by Steyn et al (2021b, Table 3), who estimate the deaths from covid-19 in New Zealand within one year at 3,539 if 90% vaccination of the 12+ group were achieved and minimal other measures to contain the virus were adopted (test, trace, isolate and quarantine). This figure of 3,539 is based inter alia on the IFR data from Verity et al (2020). As argued above, that data overestimates the IFR by 100%. So, the appropriate figure is 1,800 deaths. Of these 1,800 deaths, some would be amongst the 10% of adults who were unvaccinated (in their analysis) and these must be deducted because they are irrelevant to the current analysis. Steyn et al (2021b, Table 1) adopts an estimate of 94% for the effectiveness of the vaccine against severe disease. I assume the same effectiveness against death from covid-19, in their analysis. So, with a 90% vaccination rate, for every 10 deaths amongst the unvaccinated, there would be 90 amongst the vaccinated if the vaccine were completely ineffective and 90*(1 – 0.94) = 5.4 taking account of the vaccine’s 94% effectiveness. Consequently, of these 1,800 deaths, the proportion vaccinated would be 5.4/(10 + 5.4) = 0.35. This implies 1,800*0.35 = 630 deaths amongst the vaccinated. Not all of these deaths would be due to the unvaccinated pool, and even fewer due to the subset of the unvaccinated that would accede to being vaccinated in the face of the penalties. So, the number of deaths amongst the vaccinated due to the existence of the unvaccinated who would accede to being vaccinated in the face of the penalties is up to 630.

Thus, using the figure of up to 630 deaths amongst the vaccinated implied by Steyn et al (2021b) or even up to 3,400 deaths from the earlier analysis, failure to adopt a mandating policy will not lead to at least 5,200 additional deaths from covid-19 amongst the vaccinated. This threshold figure of 5,200 presumes that the quality of life impact on the objectors is only 1% per year for five years. If it were 2% per year, the threshold for covid-19 deaths amongst the vaccinated would double to 10,400. If the unvaccinated pool had little effect on the rate of infection amongst the vaccinated (because of transmission amongst the vaccinated), the number of additional covid-19 deaths amongst the vaccinated arising from failure to adopt a mandating policy would be close to zero, which further undercuts the merits of a mandating policy.

The Case of Health Workers and Education Workers

The set of workers for whom failure to vaccinate leads to loss of their job includes health workers, of which there are currently about 213,000 in New Zealand (Ministry of Health, 2020, page 1). The cost-benefit analysis for them differs from that of the general population because they come into frequent and close contact with large numbers of sick people, who are the prime targets of covid-19. If the proportion of health workers who are vaccine resistant is the same as for the general adult population (10%), this would imply 21,000 people. However, health workers are likely to have a very low proportion of objectors, because they are accustomed to being directed by their employers on patient safety related matters. Suppose the proportion is instead 2%, which implies 4,000 people. Since loss of their jobs would impose a substantial loss upon them, I presume that virtually all of them would comply with a mandate.

In the previous section, failure to mandate the vaccine would lead to up to 630 deaths amongst the vaccinated. The QALY losses resulting from this (630*5*0.8 = 2,500) are less than the QALY losses from the 420,000 objectors being subject to penalties (420,000*5*0.01 = 21,000) and therefore mandating is rejected for the general population. However, without mandating, suppose a small subset of these 420,000 unvaccinated adults (the 4,000 health workers referred to above) would be responsible for a disproportionate fraction of these 630 deaths because these 4,000 workers are collectively in frequent and close contact with most of the 630 susceptible people. In particular, suppose in the absence of mandating that they would be responsible for half of these deaths (315 people). In this case the QALY losses resulting from these deaths (315*5*0.8 = 1,260) would be more than the QALY losses from these 4,000 being subject to penalties (4,000*5*0.01 = 200) and therefore mandating would be warranted for these 4,000 people. In fact, if these 4,000 health workers were responsible for half of the 630 deaths, their QALY losses per person per year for five years could be as large as 6.3% (rather than the figure of 1% used up until this point) before mandating was no longer optimal.

This analysis does not imply that vaccination should be mandated for health workers, because the 630 vaccinated people who might die might do so even if there were no unvaccinated people, i.e., they could all be infected through transmission of the virus amongst vaccinated people. However, unlike the case for mandating vaccines for the adult population in general (which is not supported by a cost-benefit analysis), it is possible that mandating vaccination for health workers is supported by a cost-benefit analysis as shown in this section.

The set of workers for whom failure to vaccinate leads to loss of their job also includes education workers. Unlike health workers, education workers do not come into frequent and close contact with large numbers of people who are the prime targets of covid-19. So, the argument for mandating the vaccine for health workers does not apply to education workers. In fact, the argument for mandating the vaccine for education workers is even weaker than it is for the adult population in general, because the kinds of people that education workers encounter in their jobs (those under 25) are the least likely to succumb to covid-19. Since there is no case for mandating the vaccine amongst the general adult population, there is no case for mandating it amongst education workers.

Conclusions

Vaccine mandates for the general population are proving to be extremely controversial. Opponents point to the right to choose whether to be vaccinated, and to concerns over the safety of the vaccine. Proponents point to the costs that the unvaccinated impose upon the vaccinated, most particularly the increased risk to vaccinated people of death by covid-19 (because the vaccine is imperfect). This is yet another example of the trade-offs we face in life, individually or socially, and is therefore capable of being illuminated (and possibly resolved) by cost-benefit analysis. This paper has sought to do so and the conclusions are as follows.

Firstly, opposition to covid-19 vaccines is rational for many people. In particular, the risks of death from covid-19 if infected are so low for healthy adults under the age of 50 (less than 1/50,000) that such people could rationally prefer not to be vaccinated purely on the basis of the number of serious side-effects from the vaccine that have been reported to date by Medsafe. Secondly, if the adverse impact of mandating on those objecting to vaccination were as small as a reduction in their quality of life of 1% per year for a period of five years, mandating would only be justified if failure to do so led to a pool of unvaccinated people whose existence induced at least 5,200 additional deaths from covid-19 amongst the vaccinated. Thirdly, this figure of 5,200 is implausibly high even if the unvaccinated were entirely responsible for infections amongst the vaccinated. This implies that mandating is not warranted. Fourthly, if the adverse impact of mandating on those objecting to it were larger than a reduction in their quality of life of 1% per year for a period of five years, then mandating would be even less justified. Fifthly, unlike the general population, health workers come into frequent and close contact with large numbers of sick people, who are prime targets for covid-19, and therefore vaccine mandating may be justified for these workers. Finally, this rationale does not apply to education workers, who are even less likely than the general population to come into close and frequent contact during their work hours with people at risk from covid-19.

References

Beaudet, A., Clegg, J., Thuresson, P., Lloyd, A., and MacEwan, P., (2020). “Review of Utility Values for Economic Modelling in Type 2 Diabetes”, Value in Health, vol. 17, pp. 462-470, https://www.valueinhealthjournal.com/article/S1098-3015%2814%2900054-0/fulltext.

Best Practice Advocacy Centre, 2012. “Recommended Vaccinations for Staff Working in Primary Health Care, https://bpac.org.nz/bpj/2012/december/docs/bpj_49_upfront_pages_4-7.pdf.

Ioannidis, J., 2021. “Reconciling Estimates of Global Spread and Infection Fatality Rates of COVID-19: An Overview of Systematic Evaluations”, European Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 51 (5), pp. 1-13, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/eci.13554.

Lally, M., 2021a. “Analysis of the Cost Benefit Advice on Covid-19 Received by the New Zealand Government”, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3947437.

_______ 2021b, “The Costs and Benefits of COVID-19 Lockdowns in New Zealand”, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.07.15.21260606v1.article-info.

Medsafe, 2021a. “Adverse Events Following Immunisation with COVID-19 Vaccines: Safety Report #35 – 30 October 2021, https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/COVID-19/safety-report-35.asp.

_______ 2021b, “Adverse Events Following Immunisation with COVID-19 Vaccines: Safety Report #32 – 9 October 2021, https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/COVID-19/safety-report-32.asp#analysis.

Meyerowitz-Katz, G., and Merone, L., 2020. “A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Published Research Data on COVID-19 Infection Fatality Rates”, International Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 101, pp. 138-148.

Ministry of Health, 2020, The Cost and Value of Employment in the Health and Disability Sectors, https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/cost-value-employment-health-disability-sector-25nov2020.pdf.

Mood, A., Graybill, F., and Boes, D., 1974. Introduction to the Theory of Statistics, 3rd edition, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Nordstrom, P., Ballin, M., and Nordstrom, A., 2021. “Effectiveness of Covid-19 Vaccines Against Risk of Symptomatic Infection, Hospitalisation, and Death up to 9 Months: A Swedish Total-Population Cohort Study”, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3949410.

Pollack, F., Thomas, S., and Kitchin, N., 2020. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine”, The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 383 (27), pp. 2603-2615, https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMoa2034577?articleTools=true.

Steyn, N., Plank, M., Binny, R., Hendy, S., Lustig, A., and Ridings, K., 2021a. “A COVID-19 Vaccination Model for New Zealand”, working paper, Te Punaha Matatini, https://www.tepunahamatatini.ac.nz/2021/06/30/a-covid-19-vaccination-model-for-aotearoa-new-zealand/.

Steyn, N., Plank, M., and Hendy, S., 2021b. “Modelling to Support a Future COVID-19 Strategy for New Zealand”, working paper, Te Punaha Matatini, https://www.tepunahamatatini.ac.nz/2021/09/23/modelling-to-support-a-future-covid-19-strategy/.

Verity, R., Okell, L., and Ferguson, N., 2020. “Estimates of the Severity of Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Model-Based Estimate”, The Lancet, vol. 20 (6), pp. 669-677, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1473309920302437

Footnotes

[1] The costs that the unvaccinated impose upon themselves (in the form of an increased risk of death from covid-19) are not relevant here, because the unvaccinated have chosen to bear those risks.

[2] See https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/coronavirus-age-sex-demographics/.

[3] This comparison assumes that every unvaccinated person will be infected with covid-19 and the vaccine grants complete protection against covid-19. Neither assumption is true, but recognition of them would raise the threshold age below which vaccination is not optimal. In addition the figures given in the table are averages for each band, so 1/48,000 corresponds to a 45 year old, 1/11,000 to a 55 year old and therefore 1/50,000 would equate to approximately a 45 year old.

[4] As previously noted, the figures given in the table are averages for each band, so 1/48,000 corresponds to a 45 year old, 1/11,000 to a 55 year old, and therefore 1/50,000 would equate to approximately a 45 year old.

[5] Medsafe is the New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority (a government entity).

[6] As previously noted, the figures given in the table are averages for each band, so 1/48,000 corresponds to a 45 year old, 1/11,000 to a 55 year old, and therefore 1/28,000 would equate to approximately a 50 year old.

[7] For example, see https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/coronavirus/126992919/farewell-and-thank-you-health-board-chief-says-goodbye-to-unvaccinated-staff.

[8] See https://covid19.govt.nz/alert-levels-and-updates/covid-19-protection/. Interestingly, prior to covid-19, vaccines were not mandated in New Zealand for any contagious disease: see BPAC (2012, page 5).

[9] See https://www.statista.com/statistics/436395/age-structure-in-new-zealand/.

[10] Interestingly, the New Zealand public health system suffered excess demand even before covid-19, and this excess demand is aggravated by the poor life style choices of many people, but discrimination against them of the type applied to vaccine objectors has never been contemplated.

[11] Steyn et al (2021a, page 14) cites age-related IFR data from Verity et al (2020, Table 1) and matches it to the New Zealand population proportions by age groups, which implies an IFR of 0.95%. The same data can be used to estimate the IFR for the 12+ group, at 1.13%. Both figures are unreliable because they are based upon IFR data from March 2020 from only one paper (Verity et al, 2020) rather than from recent surveys of the literature (as with Ioannidis, 2021 and Meyerowitz-Katz and Merone, 2021). However, the increase of 19% (0.95% to 1.13%) can be applied to the preferred IFR estimate for the entire population of 0.5%, to yield 0.6% for the 12+ group.

[12] In fact, it is not even certain that the vaccine reduces transmission. In a recent High Court case, brought by four border workers who were dismissed for failure to vaccinate, evidence on this matter was presented by both parties and the judge concluded that this issue was uncertain despite being otherwise well disposed to evidence presented by the Crown and ruling in their favour: see https://www.courtsofnz.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/2021-NZHC-3012.pdf at paras 100-112.