29 April 2020

Gerhard Sundborn, Senior Lecturer Population and Pacific Health, The University of Auckland.

With Covid-19 bearing down on New Zealand, and fears of an overloaded health system and a death toll numbering many tens of thousands, the Government moved swiftly to implement a national lockdown. The magnitude of this threat is now being questioned by many epidemiologists and statisticians, here and internationally.

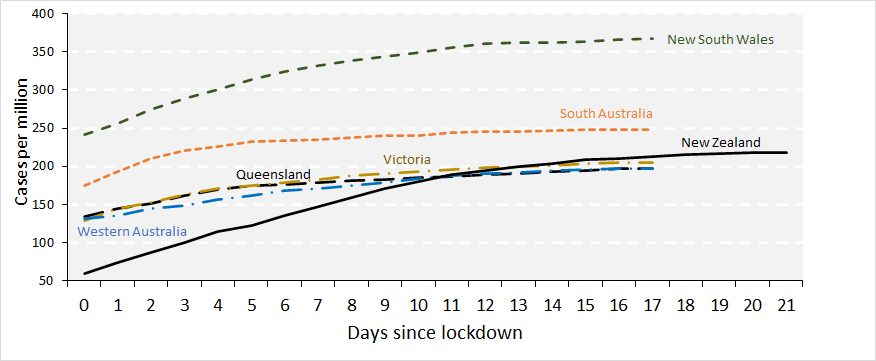

Although the lockdown was administered with the best intentions at heart, we at Plan B propose that the stringent five-week lockdown went further than necessary. Consequently, there are real questions to be asked about whether the benefits of the lockdown justify the negative social and health impacts. There is also doubt as to whether draconian measures such as lockdowns are any more effective than less severe measures such as social distancing.

Impact on Health Care Services

A clinician at a local hospital explained that they have been temporarily closed during level 4 and have been working out of a sister hospital nearby for acute patients only. When their hospital re-opens, to clear the accumulated backlog of surgical procedures and investigations it may take at least one to two years’ work including weekends to get back on track.

There are many reports of similar occurrences where hospitals around the country have reduced their provision of standard care and have been eerily quiet only operating at 50% of their usual capacity. The level to which life-saving and prolonging treatment and surgery has been either cancelled and delayed for many conditions including cancers, heart disease, diabetes, fertility, joint surgery and more need to be considered when weighing up whether the lockdown has been justified or has caused more pain, suffering and death than it has prevented and how much longer this can last.

In a recent communication the medical director for the Cancer Society feared that up to 400 cancer related deaths could be seen due to significant delays in diagnostic and treatment procedures resulting from the lockdown. Overseas evidence has shown that only half as many cancer diagnoses have been made during lockdown than normally expected.

Adding to this dilemma is the bizarre situation that many general practice clinics find themselves in where they may be forced out of business due to spiralling costs and falling revenue. One clinic explained that there are significant costs placed on GP practices in acquiring the right supplies in preparation for Covid-19 as well as a significant reduction in business from the lockdown. People have delayed seeking medical advice for less urgent ailments which has meant reduced income. People have also not sought treatment for more serious conditions for fear of becoming infected if they leave the safety of their ‘home-bubble’.

Short-term health and social harms

Domestic Violence – A surge in domestic violence as a result of lockdown procedures has occurred. In the UK, calls to helplines for domestic abuse increased by 25%, visits to their associated websites increased by 150% and cases of actual abuse soared. In China’s Hubei province during February domestic violence reports to police tripled. Regrettably, we (New Zealand) hold the title of having the highest rate of domestic violence in the developed world, meaning that we are not immune to this second ‘silent casualty’. Police statistics showed that just three days into lockdown (Sunday 29th March) a 20% increase in reported cases of domestic violence. I am fearful to know what levels of domestic violence exist in our communities now – 5 weeks on. What do the victims – adults and children – go through and what impact will this have on their future? Added to this, some DHBs have reported rises in the number of drug and alcohol presentations to their Emergency Department and in cases of suicide.

Poverty – In the most recent Salvation Army Covid-19 Social Impact Report and Dashboard a number of measures are cause for concern, including the number of people and families that have become impoverished. The greatest increase was in the food security measure. In the third week of the lockdown, close to 6,000 food parcels were distributed. This is equivalent to what is usually distributed in one month.

Long-term health and social harms

Due to the impending economic downturn as a result of Covid-19, there are several negative health and social harms that are expected to continue over a number of years as a result of loss of jobs and higher poverty. The NZ treasury have predicted that unemployment rates could climb to twenty six percent.

At the individual level we expect increased:

- Use of primary and secondary care health services

- alcohol-related hospitalisation and death

- levels of chronic ill-health

- excess mortality from: circulatory disease; poor mental health; increased health harming behaviours; self-harm; and suicide

For families – studies have shown that following mass unemployment events there is likely to be increased:

- levels of divorce,

- conflict and domestic violence,

- unwanted pregnancy,

- levels of poorer spouse and child health,

- levels of financial hardship affecting parenting,

- strain of child mental health

- levels in lower educational attainment1

For communities the experience of mass unemployment is likely to result in less social support networks and community participation, which add to a sense of grief, social isolation and a loss of community identity.

Level 2 Now

The negative implications from the lockdown on our lives as well as on the economy are causing damage that won’t be fully appreciated for years to come. This carnage is the result of business closures, job losses, rising unemployment and the stresses that go with it.

From a public health standpoint, we need to limit the social and health harms to our society, we need to move to ‘Level 2’ immediately. We will need to wrap stronger protection around hospitals as well as elderly care facilities and develop ways in which we can better support the elderly and people with underling health conditions who are living in homes with younger family members. These initiatives will need to be carefully thought out, developed and resourced appropriately. The vast majority of our population, including most working people, students and infants, face minimal risk from the virus and can safely resume normal life.

We need to get our society up and running again and open for business. Students need to be back at school and in tertiary education and all types of workplaces opened immediately.

The sooner the ‘lockdown’ can be lifted the more businesses and jobs that can be saved, the better us all. Unfortunately, the long-term impacts of the situation we find ourselves in will need to be worked off over many years and possibly decades by ourselves and our children and will shape our lives and society in ways that we are yet to fully appreciate.