By Ananish Chaudhuri, Simon Thornley, Michael Jackson.

20/6/2020

877 words

The recent fiasco that allowed people to leave quarantine without testing, risking spread of Covid-19, highlights how nebulous the government’s claim of total elimination always was. The government, in projecting thousands of deaths that never eventuated, has continued with a story that the virus can be eliminated if we all play our part. The façade of a watertight border has been shattered, and the government broke its own quarantine rules. We urgently need to reconsider whether an ‘elimination at all costs’ strategy makes sense, as many other countries are moving on and opening up their borders.

Like other coronaviruses, Covid-19 is here to stay and a vaccine will be a long time coming. Studies show that respiratory viruses are ubiquitous. Over two years, in a cohort of 214 people who were sampled every week in New York, 70% had at least one positive test for a respiratory virus, with the vast majority having few symptoms of infection.

And even if we do get a vaccine, its efficacy is far from guaranteed. Vaccines against seasonal flu are often ineffective since we are often vaccinating against last year’s strain while the virus has already mutated.

Vaccines need to be thoroughly tested before they are offered to the populace. The usual process is to go through three phases of clinical trials. At present, only one vaccine is in phase 2, where safety and dose information is tested in a large group. The critical phase of testing efficacy (phase 3) is the most time-consuming step and often takes years. With the virus now waning in many countries, demonstrating the effectiveness of the vaccine will be difficult, since exposure to the virus will be rare. The sooner we face up to this fact, the better off we will all be. Sooner or later, we will have more cases; at least ripples, if not a wave. We will need to learn to tolerate further cases.

However, based on what we know about the virus at this point, there is no reason to panic. First, contrary to what was claimed earlier, the infection fatality rate of Covid-19 is around 0.25 percent. Many people who contract the virus show few symptoms and the age distribution of fatality with the virus is similar to day-to-day life. Serological tests are telling us that a much larger proportion of the population has immunity against the virus. Even in those who test negative, a high proportion are showing other signs of immunity, through a separate cell-mediated pathway. With more of us already protected, it is harder for the virus to spread.

Second, the most at risk are the elderly, especially those who are frail with other illnesses. This does not mean that we should be willing to sacrifice our parents and grandparents. It simply means that we need to exercise greater caution around the elderly, particularly those in care homes and in hospitals. The majority of deaths with Covid-19 have been in rest homes. Conversely, this also means that we don’t need to worry too much about the young and the healthy. Children especially seem virtually immune to the disease.

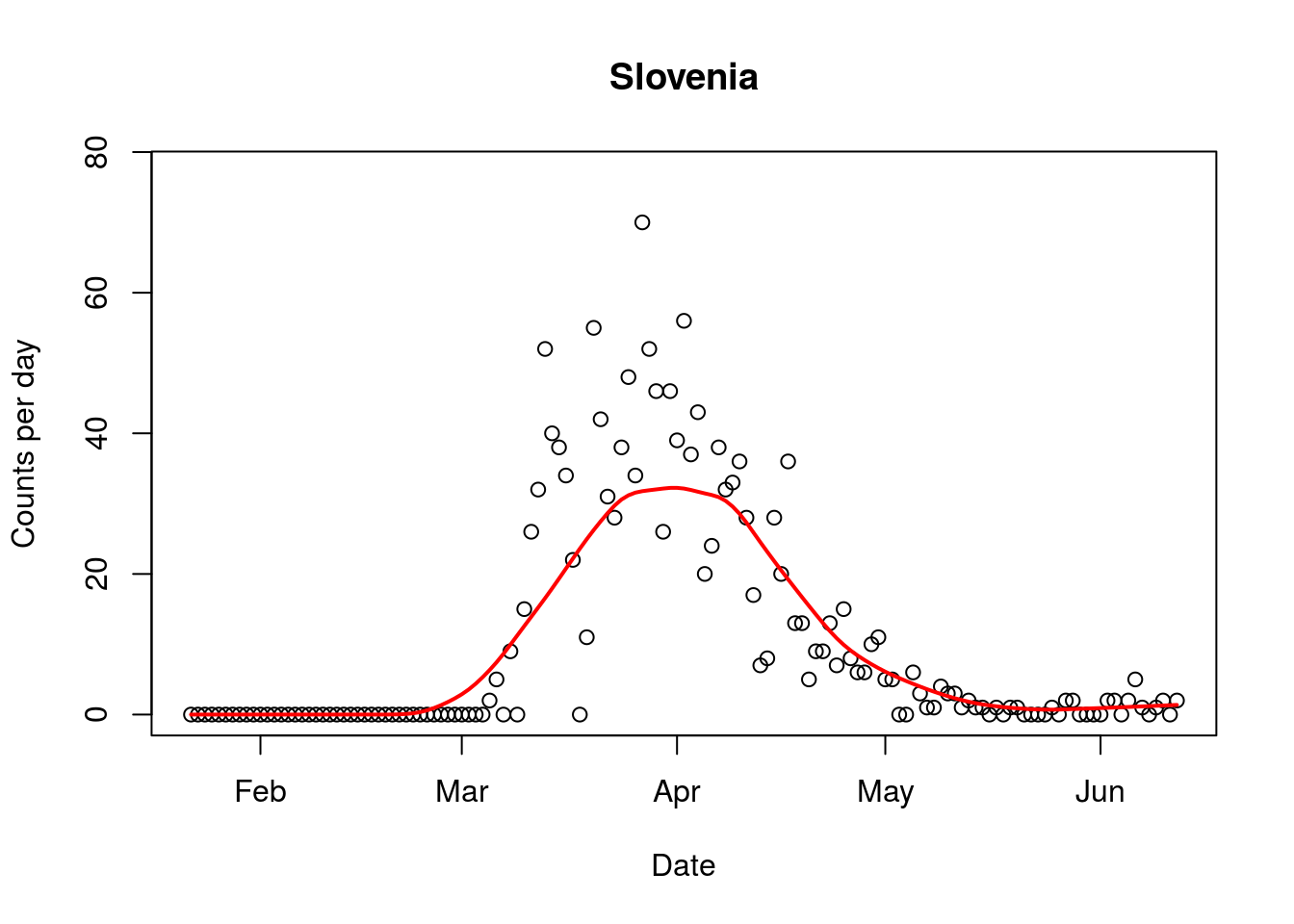

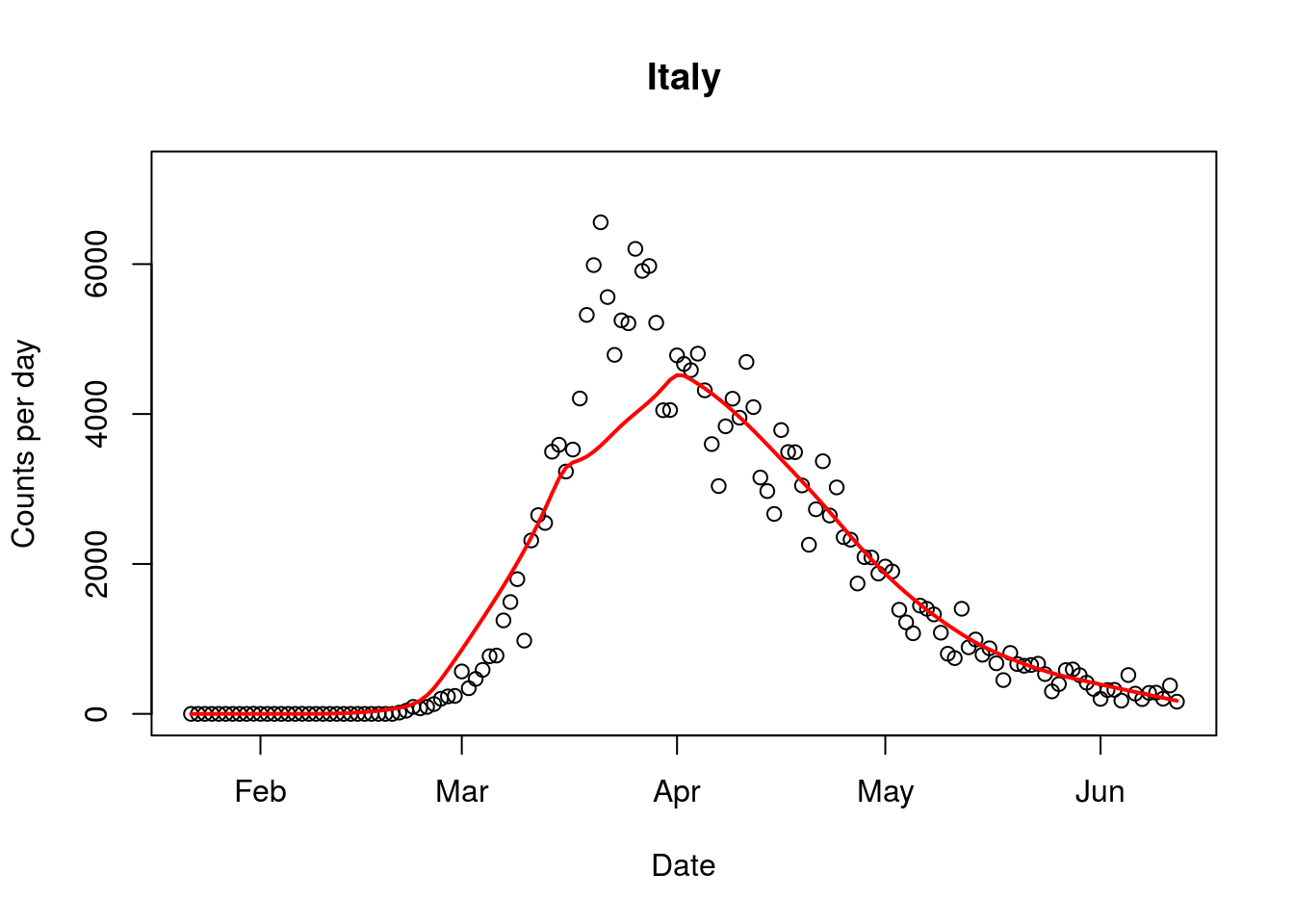

Third, countries all around the world have started opening up. Slovenia has opened its border with Italy, the hardest hit country. The government of Slovenia has declared the epidemic over and is now rather prioritising economic recovery. Across Europe countries are moving to open up their borders, as their governments reassess the risk posed by the virus.

Given this, it seems bizarre that our border is still tightly closed, even with our Pacific neighbours including Cook Islands, a state that is associated with New Zealand. The Cook Islands earns 80% of its revenue from tourism mostly from New Zealanders who holiday there.

Lockdowns are not and never were a panacea. There is very little evidence that lockdowns mitigate the spread. The theory indicates that they slow cases down, rather than reduce overall numbers. Our firm lockdown will cause a significant economic misery with public debt climbing to more than 50% of our GDP in about 2 years’ time. Unemployment will increase sharply and it is well documented that higher unemployment lowers life expectancy, not to mention potential self-harm.

Current predictions are for a 15.8% drop in GDP in the second quarter of the year, suggesting that the Finance Minister’s suggestion of a 4.8% drop during the budget presentation was underestimated.

Behind the scenes, lockdowns, here and elsewhere, are causing havoc. The evidence is emerging gradually. Required tests and surgeries have been postponed and vaccinations have been delayed. Both lives and livelihoods have taken a hit. Around the world, about 80 million children have not been vaccinated leading to a sharp increase in measles, diphtheria and cholera.

It is now time to take stock. The government has broken its own rules to eliminate the virus. Simultaneously, Covid-19 is not as dangerous as it was first thought to be. Serology tests overseas clearly show that the virus has got to many more people than appreciated. We urgently need to assess our own population’s susceptibility to the virus, as we reconsider the border question. It is time for recalibration of the threat, and to prioritise flattening the economic recession curve, rather than doubling down on a fragile and myopic vision of elimination.

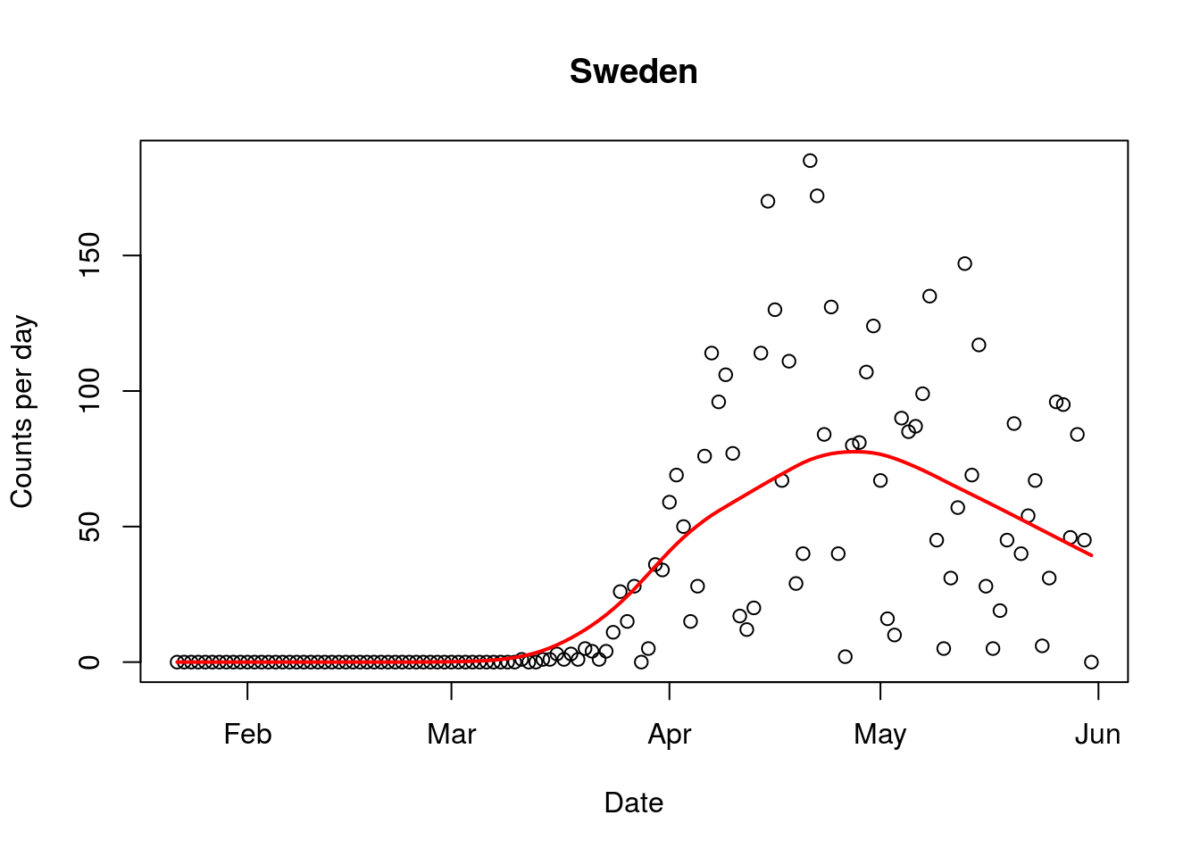

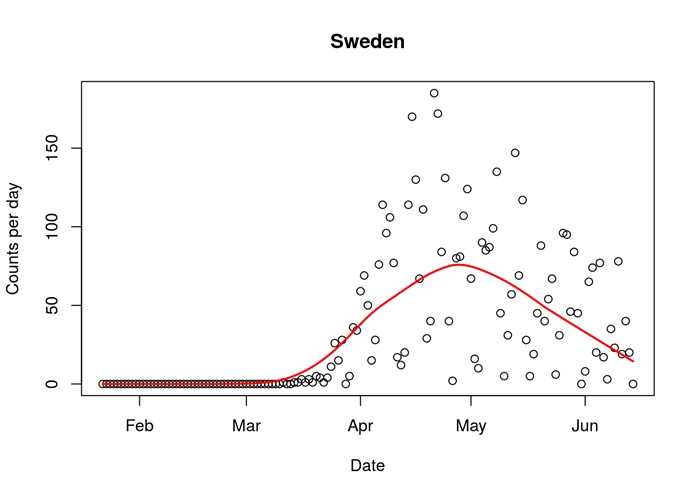

Figure. Covid-19 daily mortality in Sweden (16/6/2020). Line indicates trend.

Figure. Covid-19 daily mortality in Sweden (16/6/2020). Line indicates trend.