Simon Thornley

15/6/2020

Words: 670

In the response to Covid-19, it is easy to forget that our knowledge of the virus is provisional and still evolving. We have seen, for example, that the infection fatality rate, initially given as 3.4%, now with serology data has been dialled back considerably to between 0.02 to 0.40% which is in the range of severe influenza. This updated information brings an inevitable conflict with political decision making, in which actions are often justified at all costs.

We have now seen evidence of this, with the Medical Director of the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners, Dr Bryan Betty, stating that New Zealand was staring down the barrel of a “potential health system meltdown.” He continued: “We were literally one week away from that or we were going down a track of lockdown, which actually halted the spread of the coronavirus in New Zealand. You’ve got to remember that at that time we had exponential growth going on… [Our case numbers] were doubling every day.”

On the face of it, this sounds reasonable. We were looking down the barrel… Let’s pull out all the stops.

Several of Betty’s statements deserve scrutiny. The first is that numbers were doubling every day. They weren’t. In the days immediately before lockdown, numbers increased by 4 from 36 to 40 on the 24th of March, an 11% increase, the next day to 50 (25% increase), then level 4 was instituted. Only for one day did numbers at least double (23rd of March).

The statement that we were staring at a health system meltdown is exaggerated. During the so called “crisis”, hospitals had spare capacity. Hospitals were quiet, so quiet in fact, that specialists expressed concern about it. Intensive care units likewise. In fact, we now have the opposite problem with some primary care practitioners going broke owing to lack of demand and the costs of adapting to new service models. Patients with other conditions were clearly foregoing usual care.

The dire modelling, predicted, even with strong mitigation measures, never eventuated. If there is one thing this teaches us, it is that our understanding of the virus needs updating. The 80,000 predicted deaths are an overestimate of the observed mortality number by 3,400 times. In deciding policy responses, we desperately need to take account of the evolving nature of both the science and the available information rather than rely on outdated models.

A scientific approach involves learning from mistakes. The Norwegian Prime Minister, Erna Solberg admitted that she panicked into a decision to close schools and early childhood centres. Similarly, the Director General of Health in the Scandinavian country, Camilla Stoltenberg, stated that they could have achieved the same result by ‘not locking down’.

Here, we see both politicians and health officials learning from mistakes. Rather than being an admission of failure, it is a logical and healthy response to new information. This response contrasts strongly with some of New Zealand’s leaders.

We are rapidly learning that the threat posed by the virus is not as serious as we have been led to believe. New research shows that immunity is likely to be more widespread than we have previously appreciated. Immunity to this virus is also likely since other scientists have found cross-reactivity to other coronaviruses that cause the common cold. Many more of us are likely to have seen the virus than our case numbers indicate.

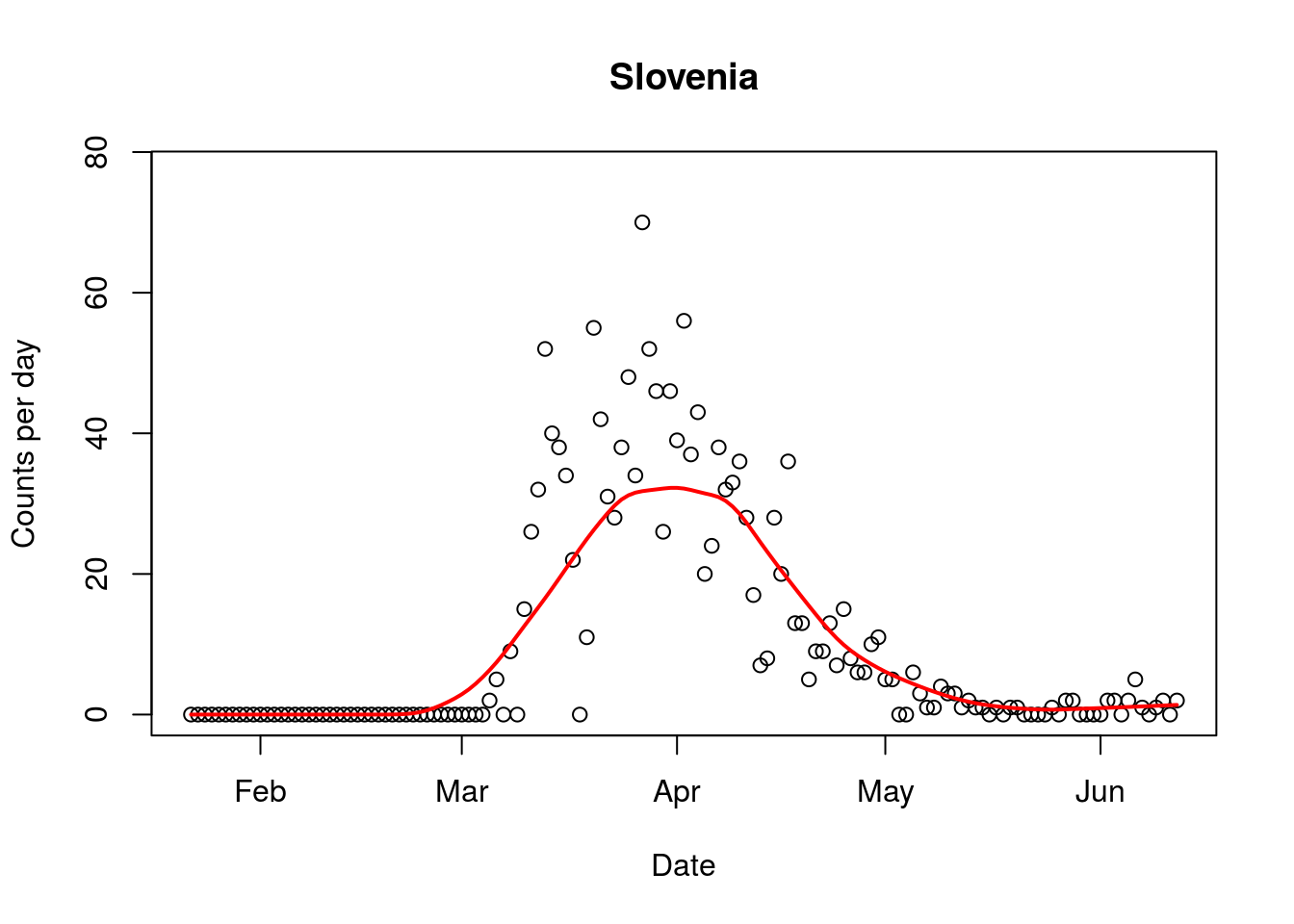

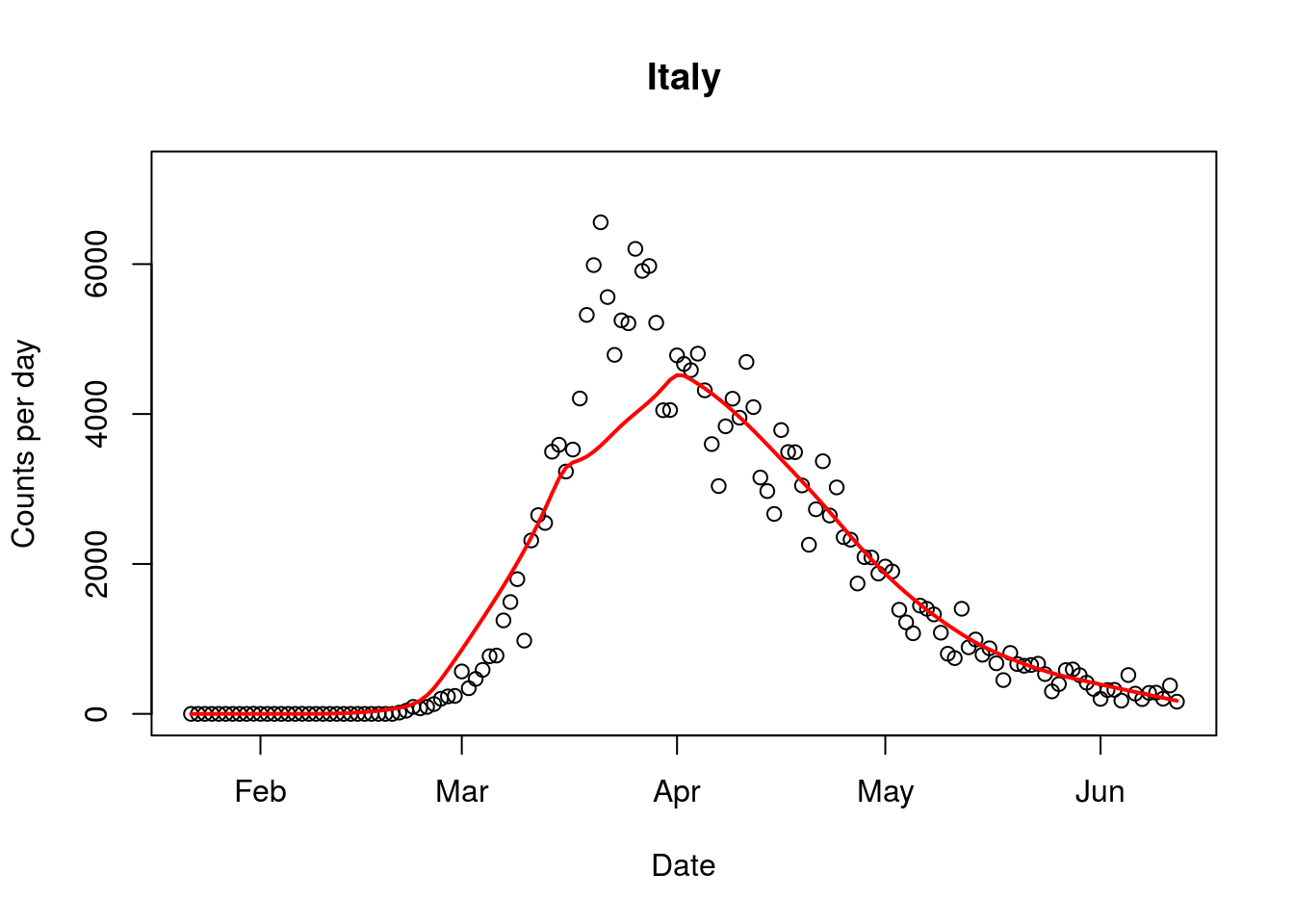

This new knowledge must lead to an update of policies for the country. We should continue to question whether it still makes sense for us to keep our borders firmly closed in the light of this new information. Serosurveys of New Zealanders would help us judge more accurately the degree of spread of the virus. If the virus has circulated to many more people than we think, and many more are protected than we previously believed, then we can have confidence to open our borders. Slovenia and Italy have already done this for several weeks and thus far they have not had second waves (figure).

Figure. Daily counts of Covid-19 cases for Slovenia and Italy, two European countries with open borders to European Union citizens.